Were Haddon the ‘head-hunter’ and Synge ‘the playboy‘ on the same side? Were they sympathetic to the de-Anglicisation project Douglas Hyde launched in 1892? If so, it would turn history on its head, but two portraits of Aran Islanders taken eight years point that way.

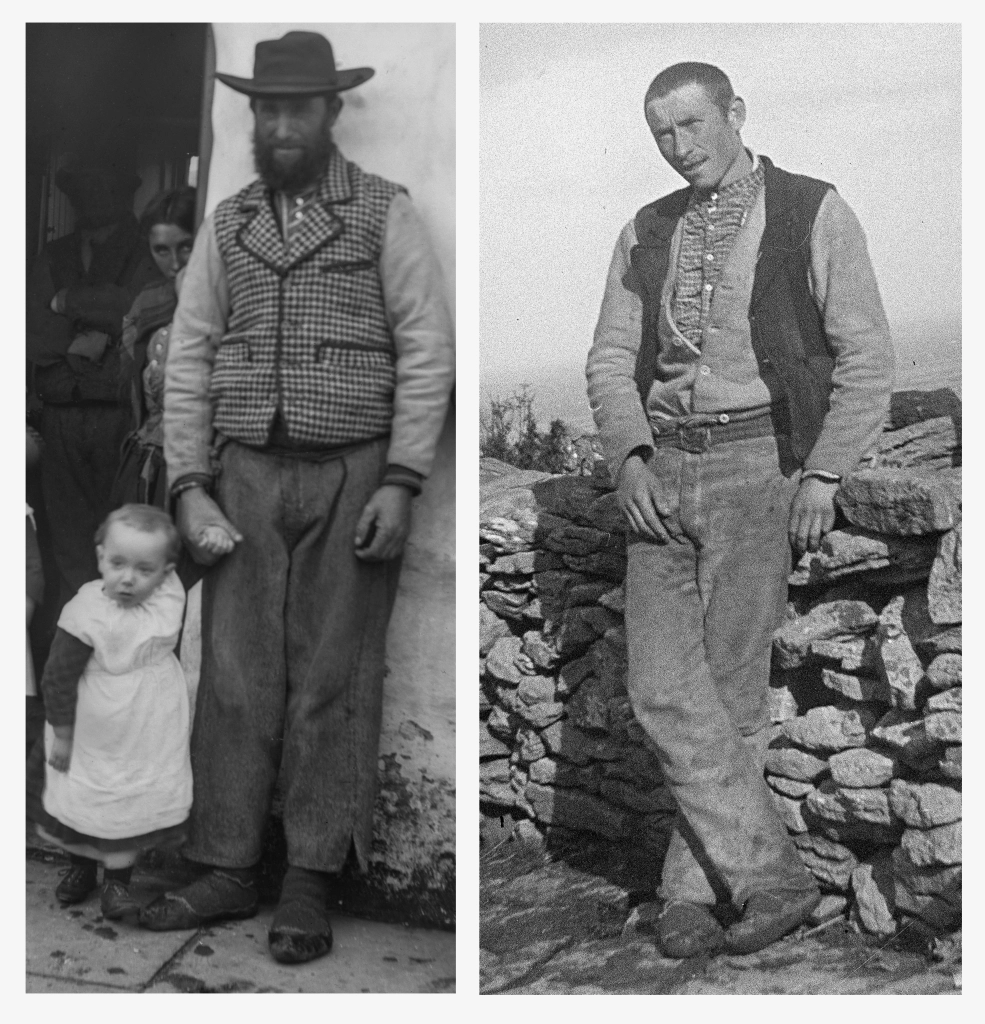

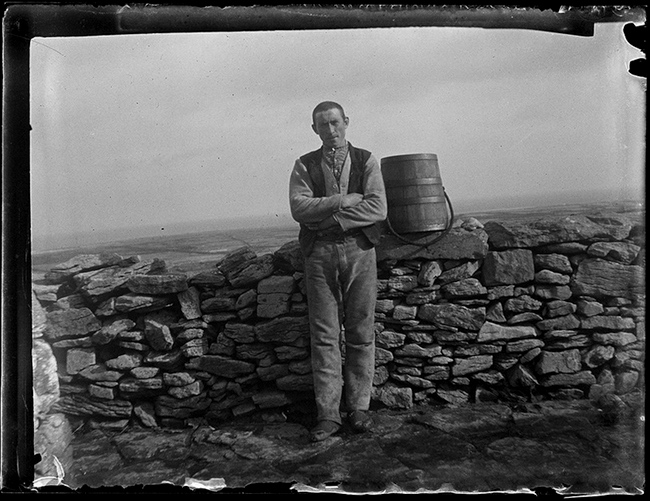

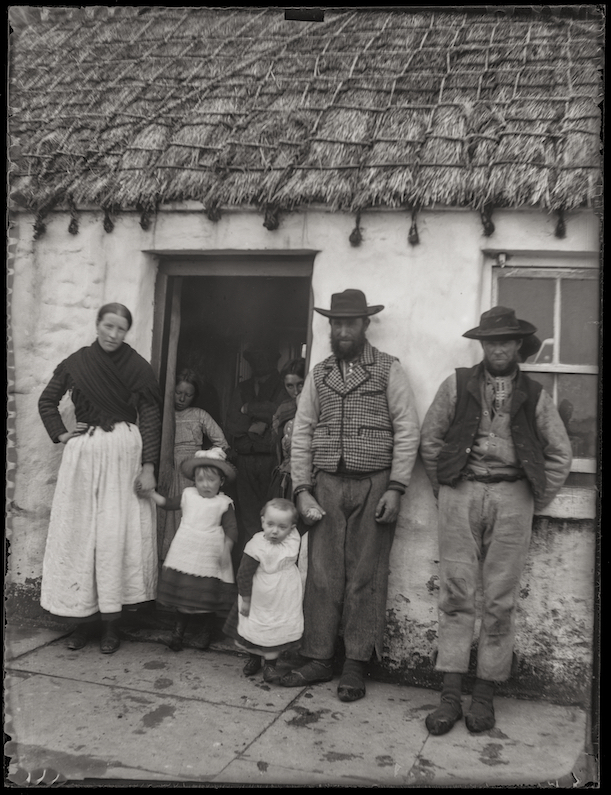

Andrew Francis Dixon took the photo on the left in 1890 in the company of Alfred Cort Haddon, a budding anthropologist who revelled in his nickname ‘the Head-hunter’. John Millington Synge took the photo on the right in 1898 at the start of a literary experiment that produced The Playboy of the Western World.

Left: A. F. Dixon. 1890. Detail of photograph printed from a digitised silver gelatine negative (Walsh & Rooney 2009, © curator.ie) The original negative is held in the School of Medicine, Trinity College, University of Dublin. Right: John Millington Synge. 1898. Detail of photograph printed from a digitised silver gelatine negative (Timothy Keefe, Sharon Sutton, Daniel Scully 2009). Courtesy of the Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

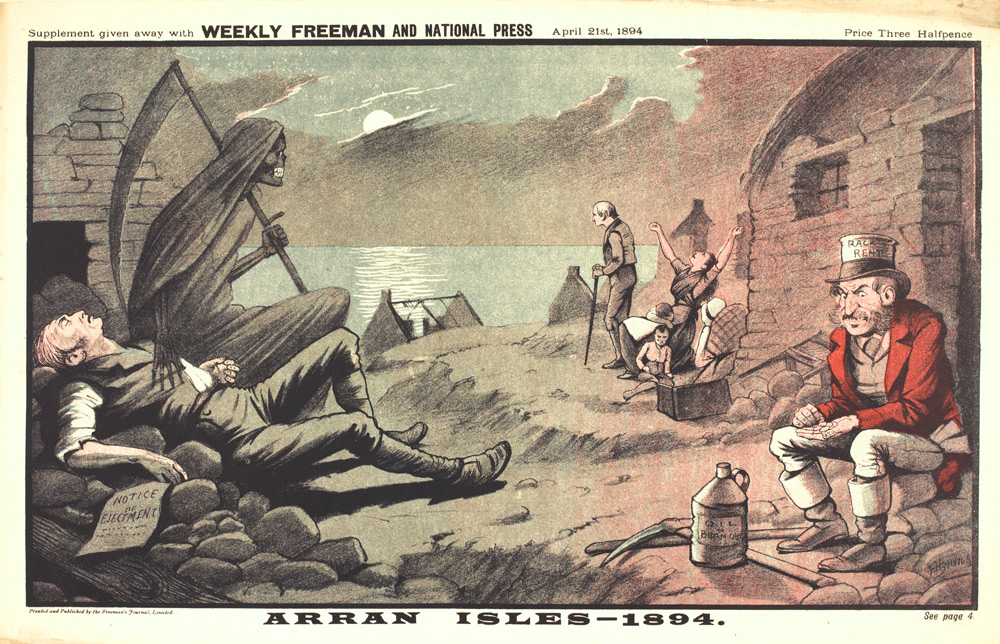

Since the 1990s, most academics have placed Haddon and Synge on opposite sides one hundred years before, when British rule and Anglo-Saxon colonisation faced unprecedented challenges from Home Rule, the Gaelic revival movement, and literary modernism. Haddon, so the historiography goes, was a colonial scientist who measured the heads of islanders in search of the racial origins of natives who refused to behave like loyal subjects of the Crown. Synge, on the other hand, lived amongst the island dwellers and turned stories of western playboys into a riotous piece of modern theatre that signalled the beginning of the end of the colonial era in Irish literature and art.

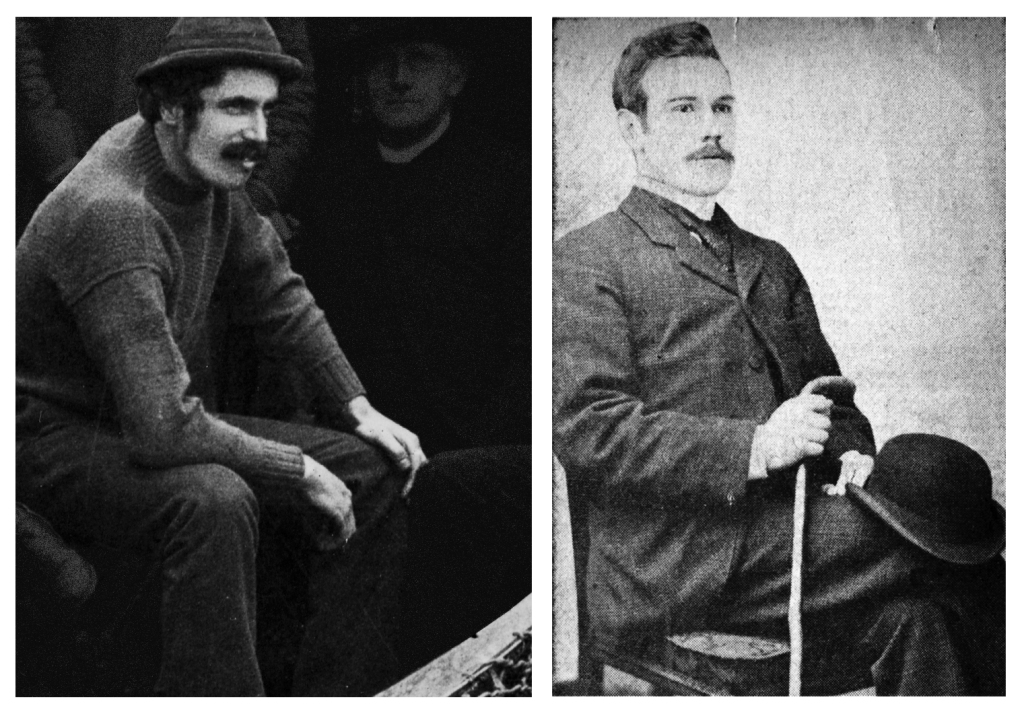

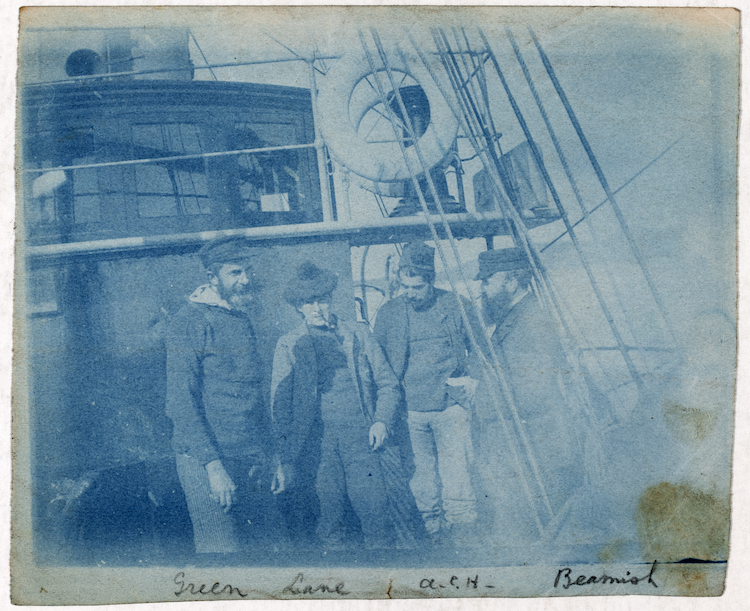

Left. Haddon on board the S. S. Brandon in 1885 (detail), with permission Royal Irish Academy © RIA. Right. Synge in Paris in 1897 (curator.ie collection).

It’s a striking contrast that suits a methodology built around binaries, but Haddon and Synge’s photographs tell a different story. I focus here on one aspect of this: Synge’s insistence that a young boy posing for a photograph wear his ‘island homespuns’ instead of his ‘Galway suit’. Ten years earlier, Haddon insisted that the people he photographed in the Torres Strait wear ‘native petticoats’ rather than the ‘calico gowns’ introduced by missionaries.

Was this a coincidence?

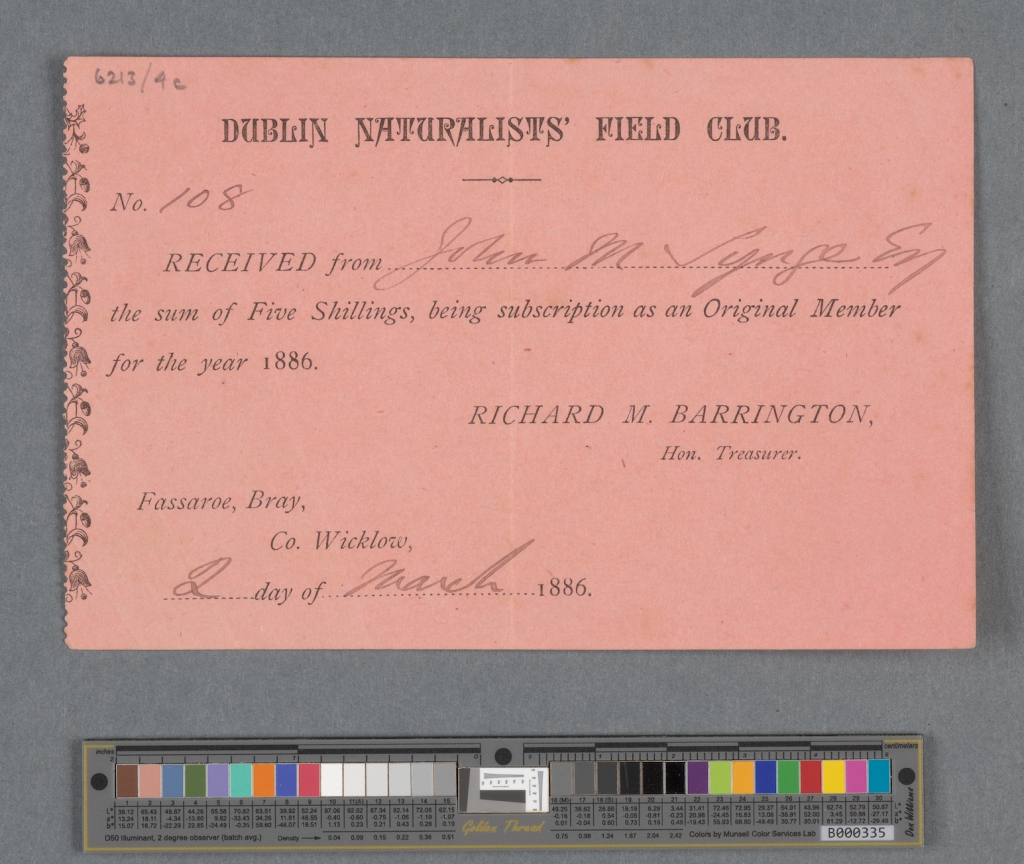

Hardly. Haddon and Synge met in 1886, when the latter – then fourteen years of age and fascinated by ornithology – became an original member of the Dublin Naturalists’ Field Club which Haddon founded. I trace the impact of that encounter in A Very English Savage and all the evidence I found points to a shared commitment to anticolonial activism as the best explanation for their rejection of the ‘Galway suit’ and the ‘calico gown’. Douglas Hyde shared the same dislike of colonial dress and in 1892 described the revival of native dress as a necessary act of de-Anglicisation in pursuit of national autonomy. That places the ‘head-hunter’ and ‘the playboy’ on the same side and in sympathy with the anticolonial campaign Hyde launched in 1892.

Lack of space meant that I presented heavily edited version of the evidence in A Very English Savage and I consider it here in more detail.

The Galway Suit

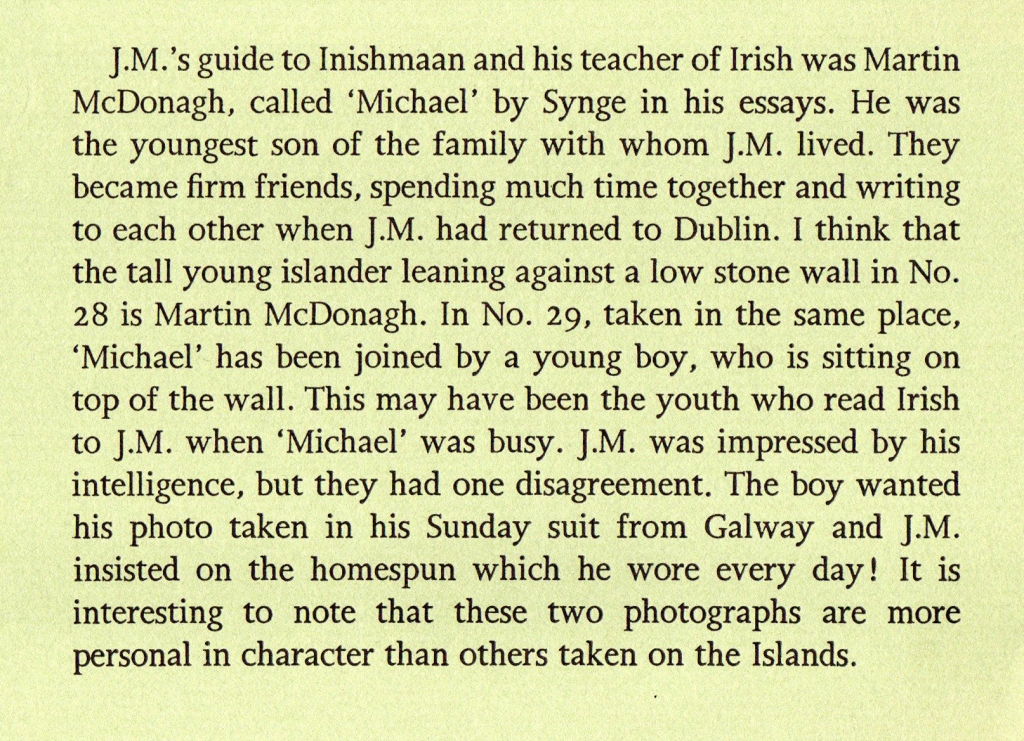

On May 10 1898, Synge boarded the The Citie of the Tribes in Galway and headed to the Aran Islands. He spent two weeks on Inis Mór, the largest island, before moving to Inis Meáin, the middle island, where he stayed for four weeks. He was an experienced photographer but he forgot his camera and bought a Lancaster ‘Rover’ from another traveller staying in the Atlantic Hotel. He took two photographs of an islander that Lilo Stephens, custodian of Synge’s photographs, identified as Martin McDonagh:

Lilo Stephens.1971. My Wallet of Photographs: The photographs of J.M.Synge arranged and introduced by Lilo Stephens, Dolmen Editions.

John Millington Synge. 1898, Digital photographs from scanned silver gelatine negatives (Timothy Keefe, Sharon Sutton 2009). Courtesy of the Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

The same story features a number of times in Haddon’s account of his first ethnographic encounters in the Torres Strait and New Guinea in 1888.

The Calico Gown

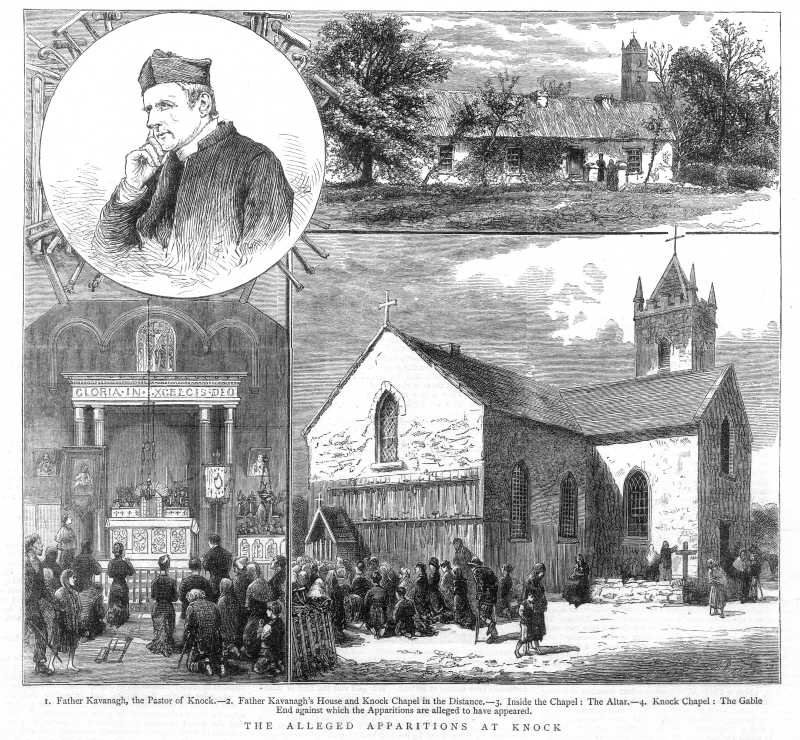

Haddon boarded the S.S. Taroba outside London in July 1888 and landed on Thursday Island (Waiben) in the Torres Strait on 8 August. He immediately set about exploring the islands that lay between Australia and New Guinea. He recorded his encounters with the islanders in his journal, sketchbooks and photographs.

He landed on Nagheer (Nagir) on 13 August and recorded that ‘The women had on calico gowns and the men trousers and shirts. What they have on when we weren’t there –if anything – I don’t know.’ He did not take a photograph because he had a small number of photographic plates with him. Five days later he photographed a group of women on the Island of Mabuaig.

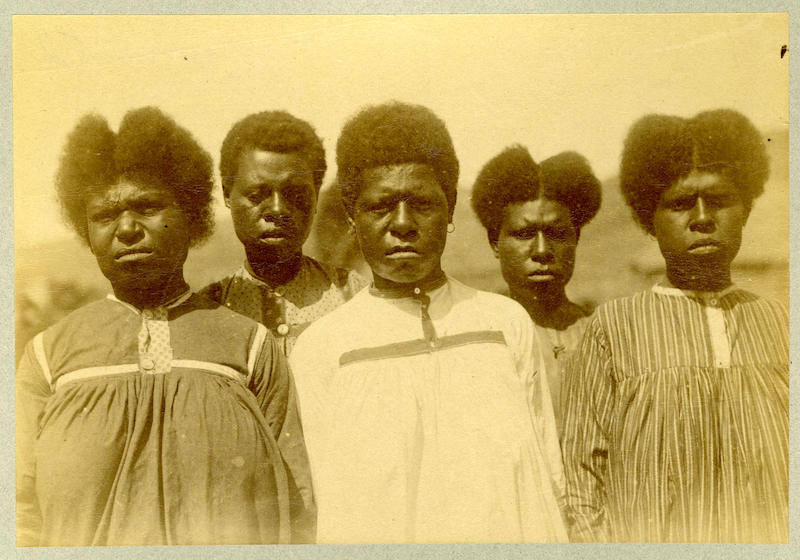

Haddon, 1888, Calico gowns, Mabuiag, Torres Strait. British Museum number Oc,B41.23. Reproduced here under a NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The following day he landed on Tudu, renamed Warrior Island in the early 1800s because of violent clashes between the islanders and the European sailors. He wrote in his journal that he persuaded the islanders

to get up a koppa-koppa or native dance for us [but] we had great difficulty in getting them to take off their respective garbs of civilisation which we knew to be (mistakenly) donned in our honour, for before we reached the village the chief [Maino] sent a man on in advance, as he subsequently admitted, to tell the women to put on the calico gowns.

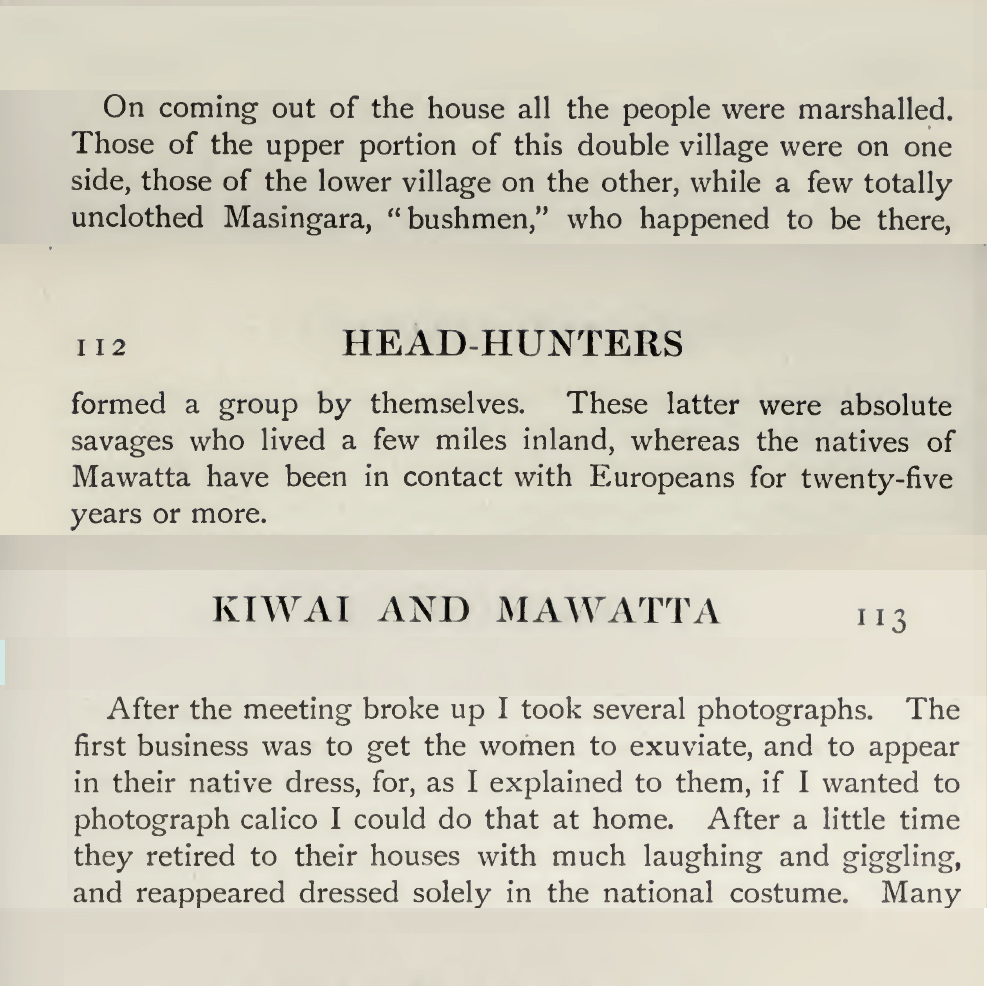

In 1901, he recalled the expedition in Head-hunters, black, white and brown and described what happened when they reached Mawatta:

Haddon, 1901, Head-hunters; black, white, and brown, p.111-112.

The presence of the Masingara “bushmen” is important because it establishes contact with populations who lived beyond the colony. His use of ‘absolute savages’ has to be read in terms of his intention to explore thoroughly ‘uncivilised’ regions inhabited by forest dwellers at a much earlier stage of social and economic development, which, Haddon argued elsewhere, could be explained by the innate conservatism of extremely isolated populations. In this context, the ‘hideous white gown’ becomes a metaphor for the disastrous consequences of contact with Europeans.

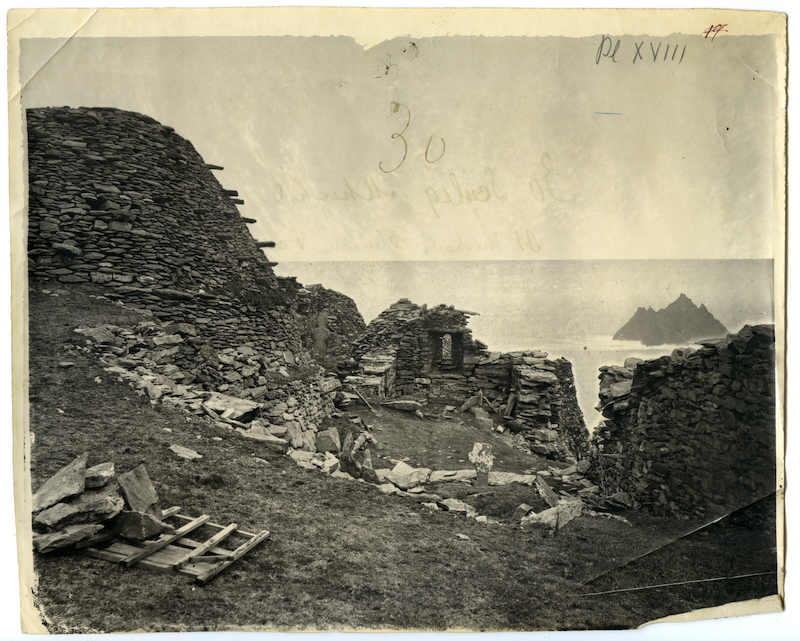

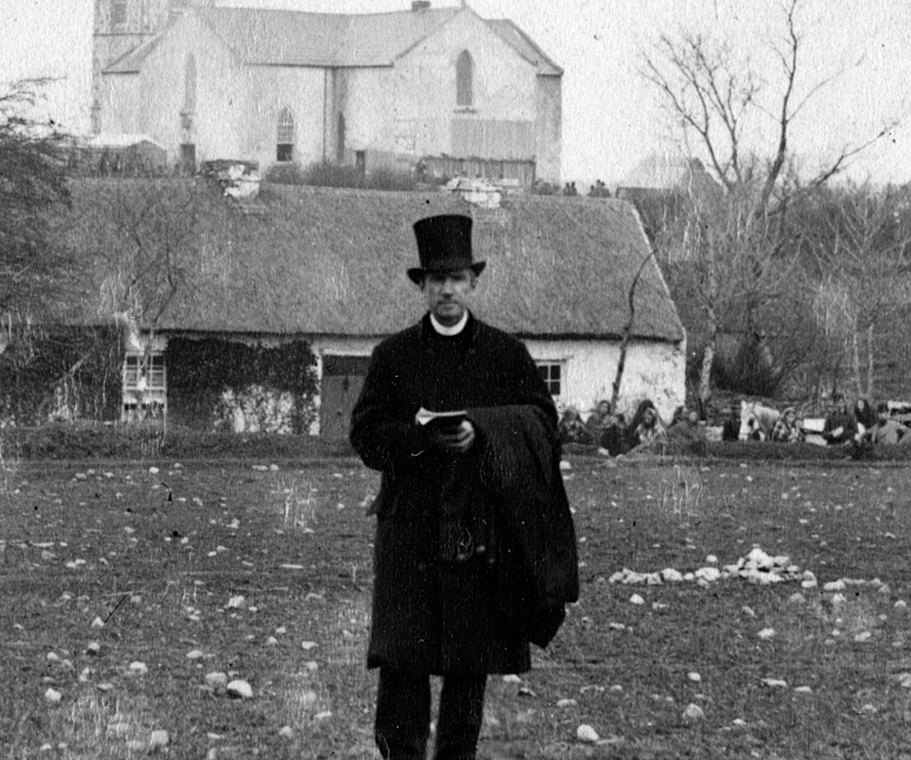

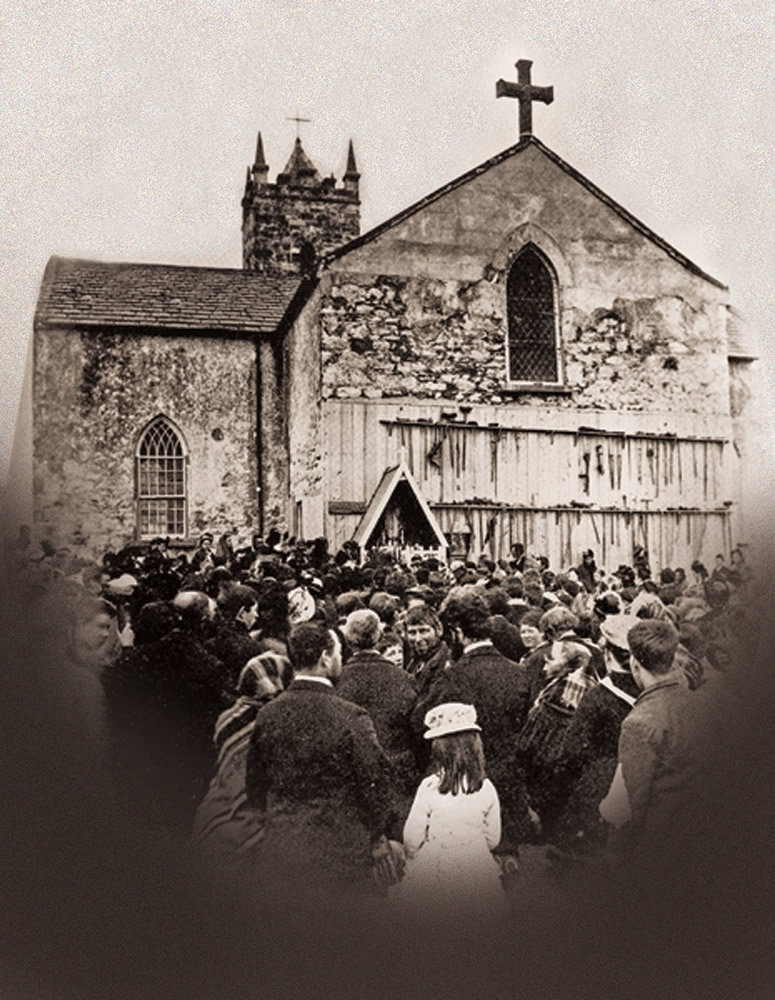

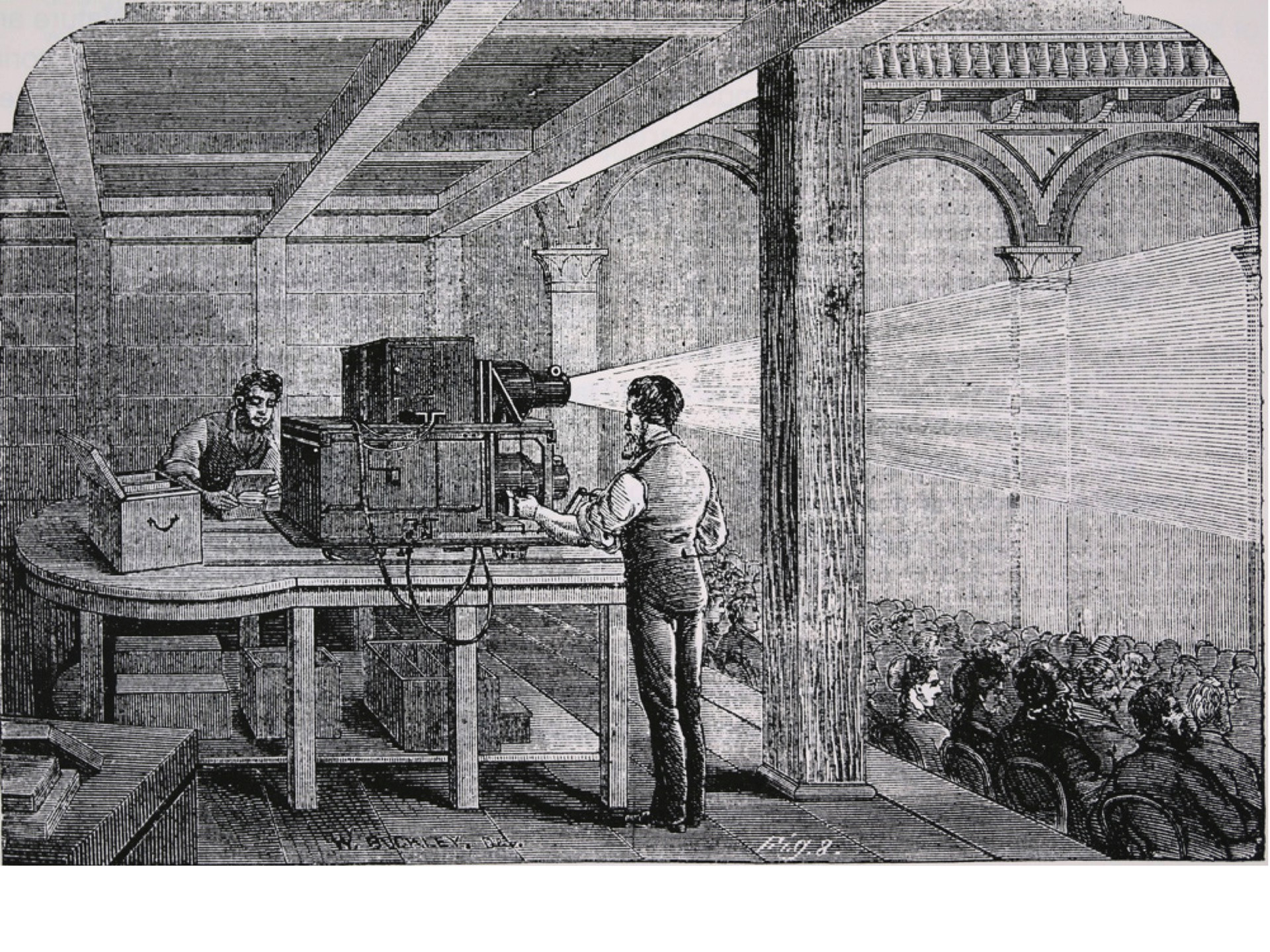

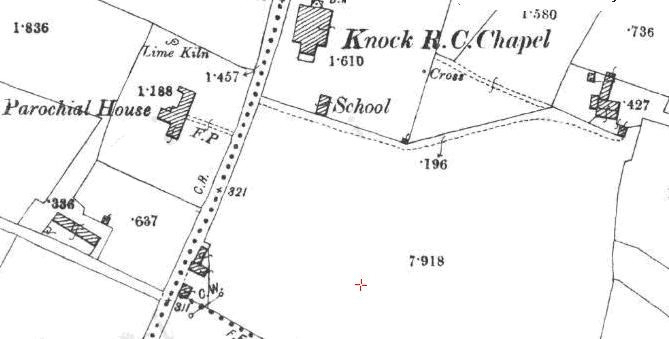

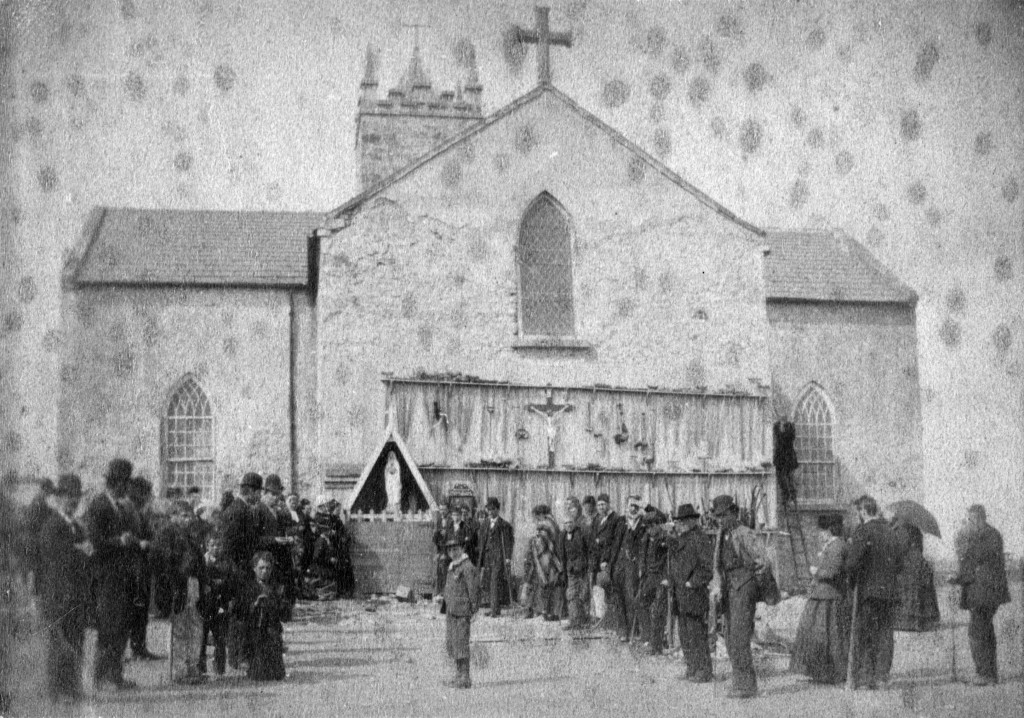

The Aran Islands were different. Haddon thought the Islands the most remarkable islands he had visited and included this description of the people in a commentary he wrote for a slide show he presented in Dublin in 1890:

The people too are a fine handsome race, upright men of good physique, ruddy complexion, fair hair and blue grey eyes, there is a large proportion of nice looking and often very pretty girls. The men wear a whitish clothes made from the locally made flannel, the costume may be entirely white or the trousers & waistcoat may be blue, coats are not often worn. The women mostly affect shirts dyed with√of a beautiful russet – red colour. In the west of Ireland the men wear boots & the women go bare footed, here both sexes xx wear native made sandles, ‘pompooties’, which they make for themselves out of cow-skins. (Haddon, 1890, ‘The Aran Islands’ manuscript, Haddon Library, Cambridge).

A. F. Dixon. 1890. Untitled. Digital print of silver gelatine, glass-plate negative (Ciarán Walsh and Ciarán Rooney, 2019 © curator.ie). The original negative is held in the School of Medicine, Trinity College, University of Dublin.

The islanders’ refusal to adopt the ‘Galway Suit’ and its female equivalent materialised, literally, the failure of the colony to disrupt folk life in the islands. Eight years later, however, the ‘Galway suit’ and cheap Paisley shawls had made inroads and Synge found himself having to persuade islanders to wear ‘national dress’ while posing for photographs. That brings Douglas Hyde into the picture.

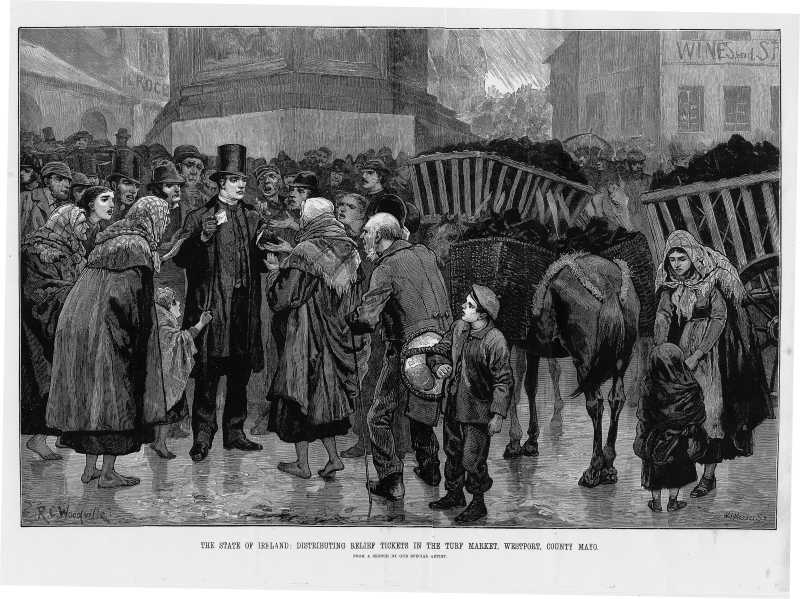

The Necessity for De-Anglicising the Irish Nation

In November 1892, Douglas Hyde addressed the Irish National Literary Society in Dublin and his treatment of ‘national dress’ is strikingly similar to Haddon’s campaign against the ‘hideous calico gown.’ Hyde asked his audience why people in Connemara wear home-spun tweed, but those in the midlands prefer imported clothes from English cities. He then issued this call to action:

Hyde, 1892, in Charles Gavan Duffy’s The Revival of Irish Literature (1894), p. 158.

Hyde, like Haddon before him, wanted to strip the natives of their shoddy, colonial dress. Again, this was not a coincidence. Between 1892 and 1895, Haddon worked alongside Hyde and members of Belfast Naturalist’s Field Club to build a folklore movement in the city. Haddon listed Hyde in his ‘little black book’ of regular contacts and, in 1895, he invited Hyde to join an excursion to the Aran Islands organised by the Irish Field Club Union.

Conclusion

Haddon and Synge visited islands where indigenous populations were under pressure from Anglo-Saxon colonisation and they adopted dress as a code for the extent of Anglicisation or, on the contrary, a refusal to be assimilated as colonial subjects. Asking islanders to remove their ‘Galway suits’ and ‘calico gowns’ was, according to Hyde, an act of necessary de-Anglicisation that places Haddon ‘the Head-hunter’ and Synge ‘the playboy’ on the same side in the fight waged by cultural nationalists and literary modernists against Anglo-Saxon colonisation.

The field club movement emerges as a key contact point between Haddon, Synge, and Hyde. Indeed, Haddon, frustrated by the failure of the emerging discipline of academic anthropology to engage with his radical anticolonial agenda, jumped the university wall and pursued his activism through the field clubs and other extra mural networks. The role the Dublin club played in bringing the ‘head-hunter’ and ’the playboy’ together will feature in part two of this blog.