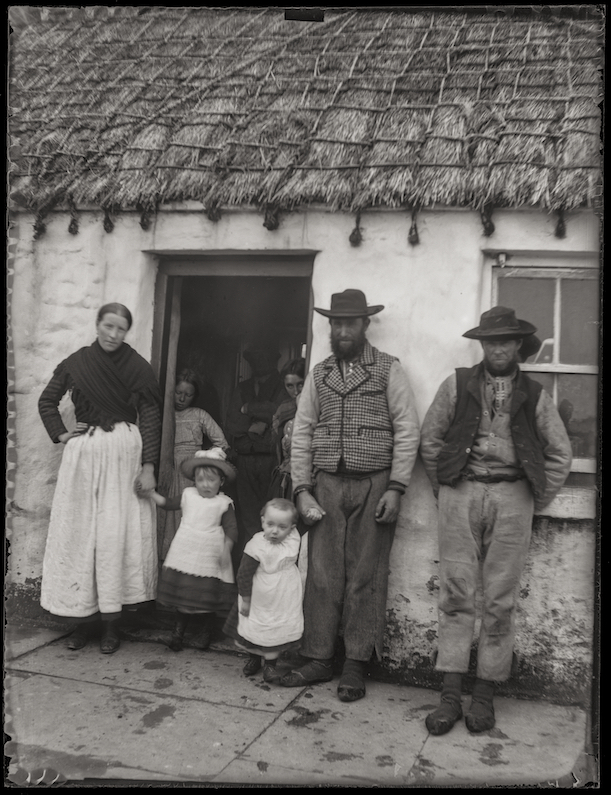

Top: Anon. 1890. Green, Lane, Haddon, Beamish. Digital print of cyanotype. MAA P.48150.ACH2, with permission of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge.

Bottom: Aran Islanders approach the S.S. Fingal in their currachs off Inis Meáin (Inishmaan – Middle Island), where islanders ferried people and goods ashore. The coast of Inis Oírr (South Island) is visible in the background. NLI VTls000284434_005 (detail), with permission of the National Library of Ireland.

Intro

Alfred Cort Haddon and Andrew Francis Dixon spent a week in the Aran Islands in 1890. They documented the glacio-karst landscape, the people, their mode of life, beliefs, customs, folklore and numerous archaeological sites. Haddon summarised the work as follows:

I can’t tell you all the excursions we made in Aran. it wd be as tedious for you to read as for me to write suffice it to say that Dixon & I left very little unseen & what with sketches & photographs we have a good deal on paper.

An entry in Alfred Cort Haddon’s journal for July/Aug 1890.

On his return to Dublin he used ten of Dixon’s photographs in a slideshow titled ‘The Aran Islands’, the first of a series that included ‘Ethnographical Studies in the West of Ireland’ in the Anthropological Institute in 1894 and ‘On the People of Western Ireland and their Mode of Life’ at a meeting of the anthropological section of the British Association later in the same year.

The exhibition is organised around Haddon’s first slideshow and develops ideas explored in my book Alfred Cort Haddon: A Very English Savage, which accompanies the exhibition and provides the focus of an RAI Research Seminar in the Royal Anthropological Institute on 31 October 2023.

A. F. Dixon. 1890. Untitled. Digital print of silver gelatine, glass-plate negative (Ciarán Walsh and Ciarán Rooney, 2019). The original negative is held in the School of Medicine, Trinity College, University of Dublin. © curator.ie.

‘Haddon and the Aran Islands’

Haddon’s first slideshow is recreated in this exhibition with photographs reproduced from digital scans of original negatives and first generation prints, most of which are exhibited for the first time. I discovered Dixon’s negatives in a storage space under the ‘Old’ Anatomy Theatre in Trinity College, Dublin in 2014. It seems the negatives were put on a shelf after R. J. Welch ‘photoshopped’ them and sent them back to Haddon and Dixon in 1890, where they remained undiscovered until 2014.

In 2019 I commissioned Ciarán Rooney | Filmbank to print a new set of photographs from digital scans of the negatives. The photographs form the core of A Very English Savage but photography is very restricted in academic publishing, so, as a curator by trade, I developed this aspect of my research as an exhibition of early social documentary photography. My intention is to show that Haddon was an artist who adopted photography as a form of ethnography and spent the next ten years pioneering the art of visual anthropology.

Top: the Haddon Dixon negative in a slotted box alongside an ‘instantaneous‘ quarter plate camera and the lightproof ‘slide‘ that held a negative, a 3¼ × 4¼ (83 × 108mm) glass slide covered in photographic emulsion. each negative was inserted into a slide before it was mounted on the back of the camera. The front of the slide was withdrawn and the negative exposed to light by removing the the cover of the lens. The operation was reversed and the slides stored for processing in a dark room or photographic laboratory. The photograph of the people of Inis Meáin is most likely a first generation contact print made by placing the processed negative on a piece of paper covered with photographic emulsion. This photograph was probably the last taken from the negative before Ciarán Rooney scanned the negative and printed a digital photograph in 2014. Bottom: the storage space under the ‘Old’ Anatomy Theatre in Trinity College, Dublin where the box of negatives lay undiscovered between 1890 and 2014. The infamous ‘Skull Passage’ on the right. (Photos: © curator.ie)

The social documentary quality and archaeological focus of ‘The Aran Islands’ slideshow disrupts the prevailing association between photography in anthropology and the scientific racism materialised in anthropometric portraits from the same era, which Andrei Nacu explored in his ‘Grid’ exhibition in the RAI in September 2023. Haddon intended to be disruptive. He had no interest in physical anthropology. His slideshow was a synthetic study of place-work-folk, a formula Patrick Geddes adapted from the social survey model Frédéric le Play developed in France.

A. C. Haddon. 1892. Michael Faherty, and two women, Inishmaan. Digital print of a silver gelatine print that Charles R. Browne pasted into an album in 1897. TCD MS10961-4_0007, courtesy of the Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin. Haddon took another shot of this group and reproduced it as Figure 7 on Plate XXIII of “The Ethnography of the Aran Islands, County Galway.” TCD MS10961-4_0007, courtesy of the Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

The sociological framing of Haddon’s ethnography was unprecedent and inaugurated a formal opposition between ‘instantaneous’ or social documentary photography and what Haddon, writing in a photo-ethnographic manifesto in the 1912 edition of Notes and Queries on Anthropology, called the ‘stiff profiles required by the anatomist’. As brief as it is, this statement matters for two reasons. One, it registered Haddon’s long battle with the anatomists who dominated anthropology in the 1890s. Two, it expressed his commitment to visual anthropology as a sociologically oriented alternative to physical anthropology and, as such, an ethnographic vehicle for anti-colonialism activism.

Haddon set up this selfied ofCharles R. Browne measuring Tom Connelly’s skull while Haddon enters the information into specially prepared index cards.Courtesy of the Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Sure, Haddon engaged in skull measuring in a mobile version of Francis Galton’s anthropometric laboratory when he returned to the Aran Islands in 1892. He also produced ‘stiff portraits’ as he tried to establish himself in a field dominated by Galton and his associates, including Alexander Macalister, Professor of Anatomy at Cambridge and President of the Anthropological institute from 1893 to 1894. In 1893, Macalister employed Haddon as a part-time lecturer in physical anthropology and, in 1895, they managed an ethnographic survey in the village of Barley. Haddon took photographs following guidelines Galton drew up for the UK Ethnographic Survey.

The contrast with ‘The Aran Islands’ slideshow couldn’t be starker and that situates Haddon’s experiment in a wider struggle between ‘culturals’ and ‘physicals’ – as E. B. Tylor (1893) labelled them – for control of anthropology. Despite his ‘anthropometric’ associations Haddon was a ‘cultural’. Anthropometric portraits play little or no part in the slideshows he performed between 1890 and 1895. Instead, the slideshows document the study of folk, their customs, beliefs, art and dance across time and space, culminating in experiments in colour photography and ethnographic filmmaking in the Torres Strait in 1898.

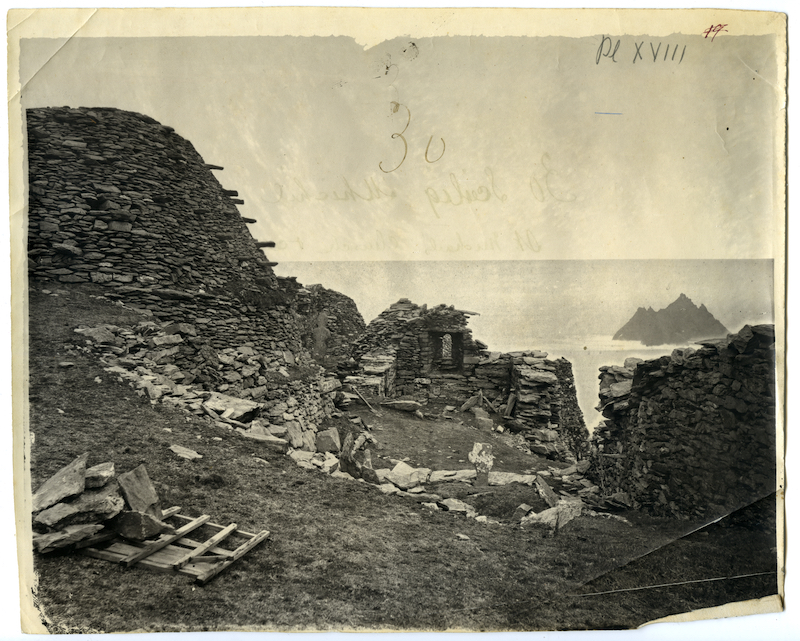

These experiments are signposted here with digital prints of the oldest surviving photograph of Skellig Michael (1868) and a copy Haddon made in 1890, a study of folk dance by Clara Patterson (1893) and a still from Haddon’s film of the last dance of the Malu Zogo-Le (1898). John Millington Synge followed Haddon to the Aran Islands in 1898 and is represented by a photograph that registers Haddon’s influence on literary modernism and cultural nationalism in Ireland in the 1890s, which, in turn, indexes Haddon’s modernism.

William Mercer. 1868. St Michael’s Church and Cell. Digital print of silver gelatine print. Mercer photographed archaeological sites for Wyndham-Quin, 3rd Earl of Dunraven, whose Notes on Irish Architecture (1875) Margaret Stokes brought to print after his death in 1871. MSA 239, with permission of the Royal Irish Academy © RIA.

Clara Patterson. 1893. Green Gravel. UFTM L2239-3, with permission of National Museum of Northern Ireland

A. C. Haddon. 1898. The Dance of the Malu Zogo-Le. Digital print of a still from the short film Haddon shot on the island of Mer (Murray), Torres Strait. Permission of National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

J. M. Synge. 1898/2009. Islanders of Inishmaan. Digital print from scan of glass plate negative (digitisation by Timothy Keefe, Sharon Sutton, Gill Whelan, printed by Daniel Scully). TCD MS11332_28_b courtesy of the Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

In sum, ‘The Aran Islands’ slideshow marks the beginning of a form of anthropology that we would recognise today as visual anthropology. Unfortunately for Haddon, his photo-ethnographic manifesto entered the modern era just as anthropology was becoming what Margaret Mead called ‘a discipline of words’. Furthermore, a historiographical focus on Haddon’s career in zoology obscured his interest in art and photography and so masked the beginning of visual anthropology.

An installation shot of the ‘Haddon and the Aran Islands’ exhibition in the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, London. The group of photographs on the right recreates Haddon’s 1890 slideshow with prints from digital scans of the original negative. Photo Andrei Nacu.

Note

The links between Haddon the ‘Head-hunter’ and Synge the ‘Playboy’ will feature in a separate blog.

in partnership with